Adapted from a Spring 2024 midterm essay for Media Studies 111C: Audio-Visual History. The prompt was to cover the changing relationship between subject and object using three authors from the course.

As the global culture of visuality emerged, we saw changes in the relationship between subjects and objects. Visuality refers to the meeting place of ocular vision and the mind’s eye, and through the three authors below, we find that objects and subjects are created and can morph into each other through both the vision of the ocular, and the imagination.

Subject to art + in art as object

Beginning with the subjects of portraiture and objects of portraits, we turn to de Bolla Here, the emerging society of visuality of 18th century England created subjects, sitters of portraits.

Charles Burney by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1781

Charles Burney by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1781

The well-to-do of the period were fascinated by the becoming a subject for reproduction via portrait. This is seen in the spectatorship of the process, voyeuristic in how people could see artists recreate others in waiting rooms and exhibitions; and autovoyeuristic, where Sir Joshua Reynolds would put a mirror obliquely to his canvas to allow his subjects to see themselves become representation. People of all classes were also subject to visibility beyond the frame of the painting: they attended exhibitions where they jostled and bustled, each competing against each other and the portraits to be seen, to be seen seeing art, to be seen as a “connoisseur”.

But the portrait sitters of the time also became objects, where under the gaze of self-presentation, they would gift each other their own portraits as polite courtesy, or wear miniature portraits of themselves in jewellery.

Mrs. Charles Willson Peale (Rachel Brewer) and Baby Eleanor by Charles Willson Peale, 1790

Mrs. Charles Willson Peale (Rachel Brewer) and Baby Eleanor by Charles Willson Peale, 1790

The pleasure of being subject to a gaze, therefore, just as easily becomes the pleasure of becoming a commodity, of presenting the self to others via an object. In the society of visuality of 18th century England, portraiture — both in production and exhibition — turned people into subjects under the gaze of the artist, but objects in the eyes of others.

Cartesian objectivity + rejecting feminine subjectivity

Beyond making the self into an object, we move to Descartes, who argued for the objective self. From Bordo, Descartes elevated objectivity and detachment as ideals for a humanity finding itself unmoored from an indifferent universe. In becoming separate from the body and the world, the gaze of the objective mind made objects out of originally generative, living things: it turned the female world-soul from a “she” to an “it”, reducing it to objects, mechanically-interacting matter, by assigning all generativity instead to God the Father.

More subtly, the Cartesian project of starting anew through the revocation of one’s actual childhood (during which one was “immersed” in body and nature) and the (re)creation of a world in which absolute separateness (both epistemological and ontological) from body and nature are keys to control rather than sources of anxiety can now be seen as a “father of oneself fantasy on a highly symbolic, but profound, plane. The sundering of the organic ties between person and nature — originally experienced, as we have seen, as epistemological estrangement, as the opening up of a chasm between self and world — is reenacted, this time with the human being as the engineer and architect of the separation. Through the Cartesian “rebirth,” a new “masculine” theory of knowledge is delivered, in which detachment from nature acquires a positive epistemological value. And a new world is reconstructed, one in which all generativity and creativity fall to God, the spiritual father, rather than to the female “flesh” of the world. With the same masterful stroke — the mutual opposition of the spiritual and the corporeal — the formerly female earth becomes inert matter and the objectivity of science is insured. (Bordo, 1987, p 108)

Furthermore, the objective visuality eliminated more feminine, subjective ways of looking: sympathetic understanding that comprehended by union, marriage and joining — the opposite of the detachment that this Cartesian rebirth idealized. In this world, all other than the rational, objective mind, were made to be objects, and a subjective, affective perspective was denigrated. There is little place for the subject here, one that understands the world through the affective call-and-response of a relationship, because things, in Cartesian geometry, are instead related by locatedness in a visual field, not relationships.

Objectifying the exotic + reflecting the European self

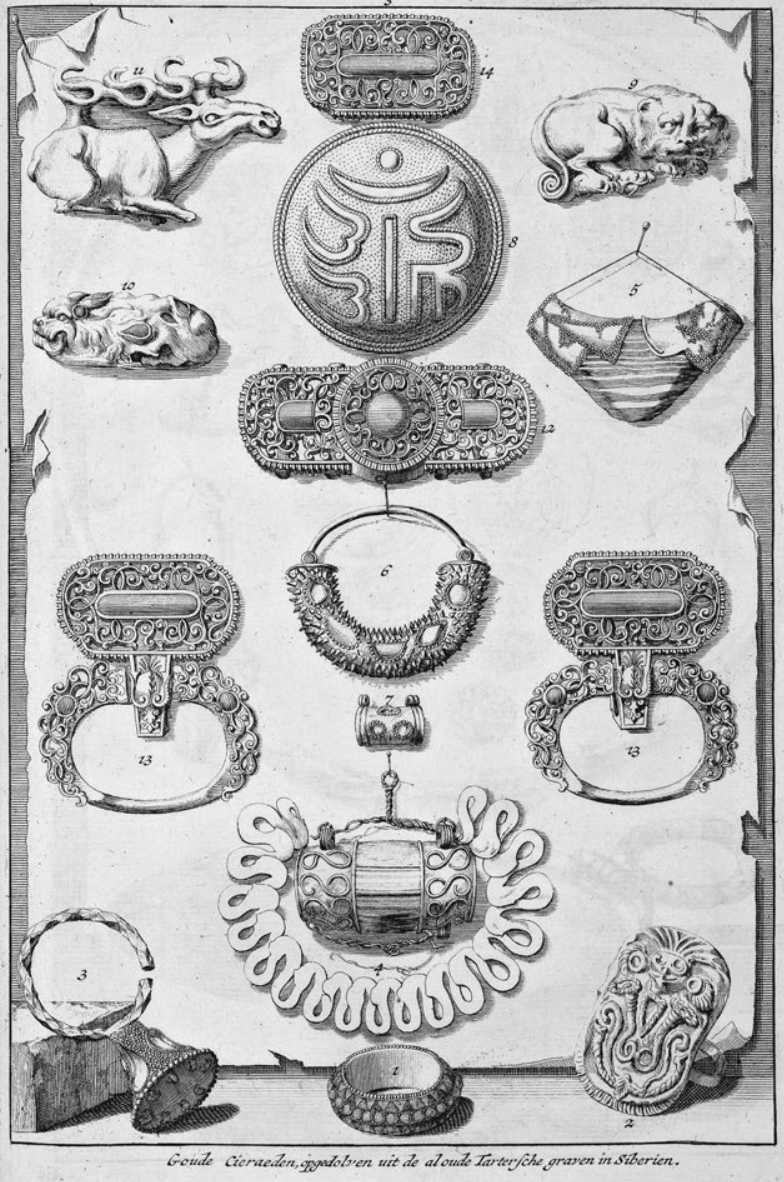

Finally, from Schmidt, the most global visuality looked beyond European shores to the exotic world. This gaze, again, makes objects of the peoples and places it lands on. Van Meurs’ atelier, for example, was known for its catalogue-style layouts of artefacts from exotic places — these allowed the sense of collectibility that led to cabinets of curiosities.

“Goude cieraeden, opgedolven uit aloude Tartersche [sic] graven in Siberien” (etching), in Nicolaes Witsen, Noord en Oost Tartarye, ofte bondig ontwerp van eenige dier landen en volken, welke voormaels bekent zijn geweest, 2nd ed. (Amsterdam, 1705; 1st ed. 1692). Special Collections, University of Amsterdam. Taken from Schmidt, p 116

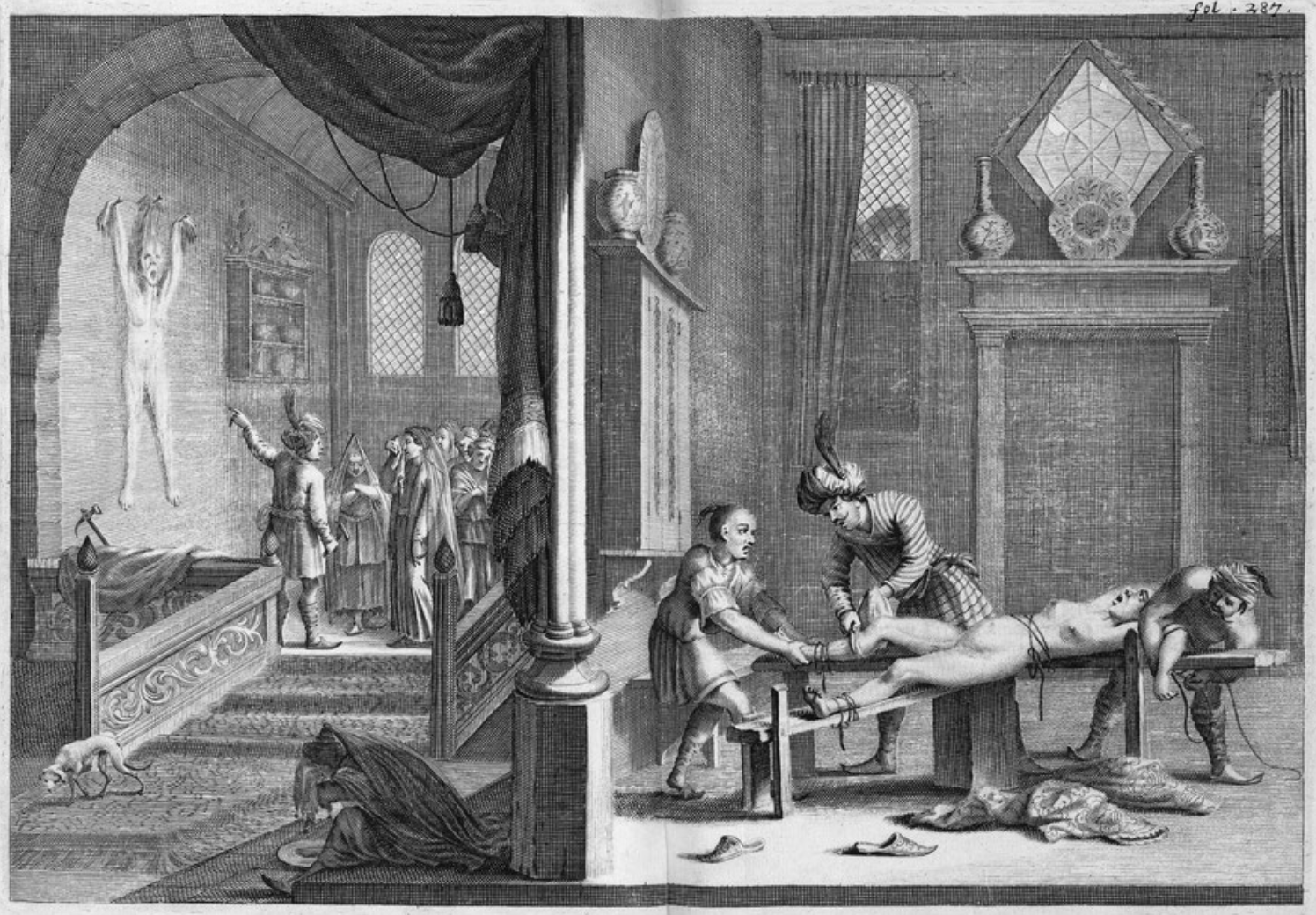

This gaze commodified and objectified people, making them canvases for clinical, post-confessional violence, and the commodification of the slave trade. The subject, therefore, could only exist within the European body: in authorial presence, in de Bruijn’s self-inserts as eye-witness to the sexual and violent spectacles of his travels. Schmidt shows Dutch exotic geography as reliant on the fantastical subjectivity of its authors and publishers and printers: a gaze that could take a sketch of a dead fish and make it almost surreal via fanciful coloring.

Jacob van Meurs (atelier), Flaying of a Polish woman (engraving), in Jan Jansz Struys, Drie aanmerkelijke en seer rampspoedige reysen (Amsterdam, 1676). Special Collections, University of Amsterdam (O 63-41).

Taken from Schmidt, p 177

Jacob van Meurs (atelier), Flaying of a Polish woman (engraving), in Jan Jansz Struys, Drie aanmerkelijke en seer rampspoedige reysen (Amsterdam, 1676). Special Collections, University of Amsterdam (O 63-41).

Taken from Schmidt, p 177

This “subject” of exotic geography is appropriate considering that the genre lent itself more as a mirror of the anxieties and desires of the Europeans than any real authentic account of the other worlds. In other words, as Dutch exotic geography made objects of the non-European world and peoples, it made subjects of its European audience, showing their lust for exotic bodies and their morbid fascination with their pain and violence.

The global culture of visuality thus makes both objects and subjects of people, depending on who is doing the looking and who is being looked at.