~ a pre-emptive mourning for this app

TikTok has been central to my obsession with algorithms for the last two years of college. Of the social media apps dominating online social life today, it is on TikTok that the presence of the algorithm seems the most obtrusive. For that reason, I wrote my honors thesis paper on it and the algorithmic imaginaries that users expressed throughout using it. Given that, I thought it would be interesting to summarize the two main reasons I use TikTok, and how those interact with my findings from my honors thesis research.

Why I’m on TikTok

I want to distinguish between two kinds of reasons why I’m still using TikTok. One would be the addictive personalization that the app’s algorithm affords me, the way it tracks my interactions and endeavors to balance between showing me new content I might like, versus old content it knows I definitely would like. This is the part of the app that has me on it for my brainrot hours, especially when I’m waiting for the bus or late at night.

But that’s not really the part of the app experience that keeps me energized in my usage of it — in that doomscrolling on TikTok for hours on end is entertaining only at the barest minimum, and honestly extremely draining for my attention span. As part of my ethnographic research study on TikTok, I would ask my interviewees — all college-age regular TikTok users — what they were thinking or feeling between videos, or during the act of swiping up to the next video. Almost all stated that they were thinking and feeling “nothing”, and were just “mechanically swiping” to the next video.

I agree, and I have those same feelings. And yet, there are some experiences that give me energy when using the app, ones that pull me out of the mechanical swiping, that make me sit up in my seat and actually engage.

Striking gold

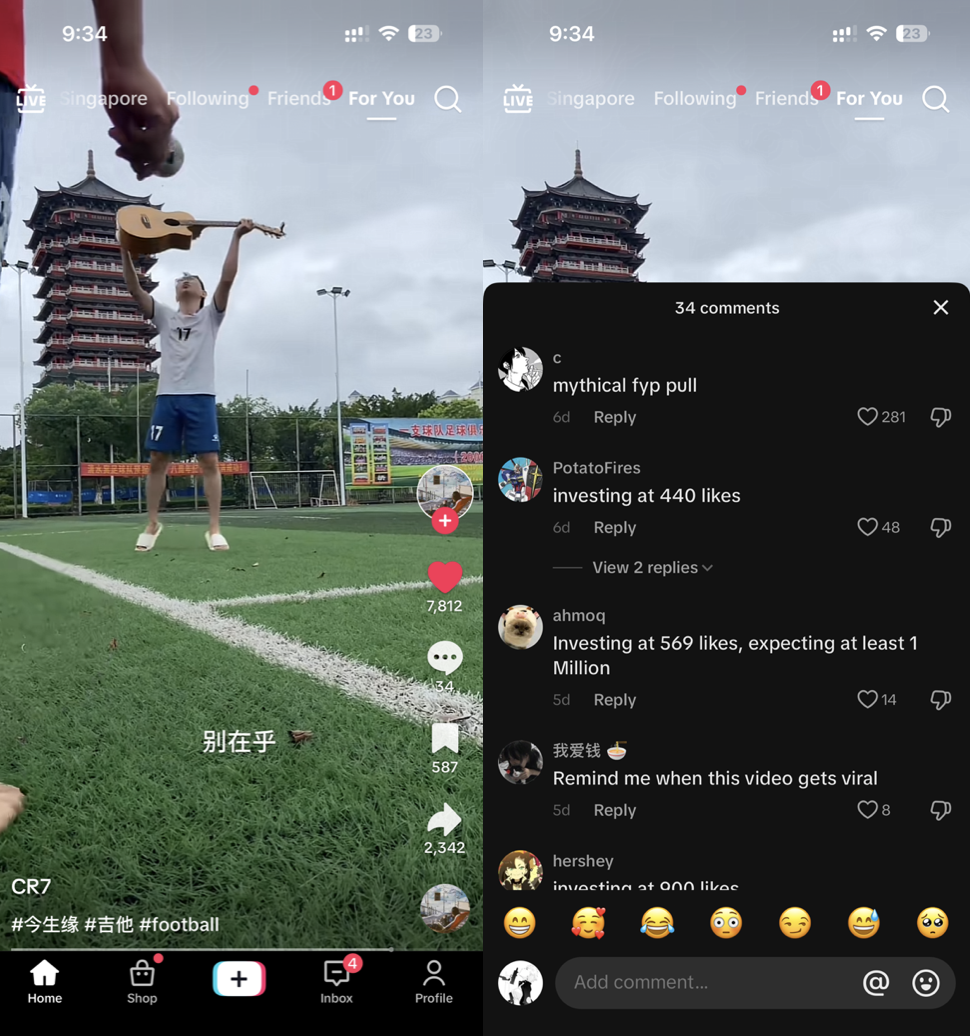

Or, as one commenter put it: “mythical FYP pulls”. I saw that comment on a hilarious video of a guy singing the song Jin Sheng Yuan (今生緣) by Luo Shi Feng / Chen Si An (羅時豐/陳思安), strumming a guitar with flying soccer balls. I can’t explain why it’s so funny, just watch it: https://www.tiktok.com/@15804701xxf/video/7377436231161957650?_r=1&_t=8nBITrylRRq

This is the kind of video I would send to all my friends and basically beg all of them to watch it and laugh with me. It’s so funny it shocks me out of mechanically swiping — probably one of those moments that you’d need to have in order to actually be convinced to use TikTok regularly. Almost like a reward for all the labor you put into swiping and swiping and swiping, to find a gem among the rubble.

the Garden & the Stream

After doing research on algorithms and algorithmic imaginaries, I’ve found that metaphors are often the most expressive ways to articulate the way we think about technologies and how to use them. A metaphor I’d use here is panning for gold: putting a pan into a stream, shaking it, sifting through it, and then finding a satisfying reward.

That metaphor actually harks back to older metaphors people used to describe the internet, specifically two alternatives: the Garden and the Stream. I’m drawing mainly from Mike Caulfield’s keynote speech for dLRN 2015 here, though there are many other sources for this.

The Garden is the web as topology. The web as space. It’s the integrative web, the iterative web, the web as an arrangement and rearrangement of things to one another.

In the stream metaphor you don’t experience the Stream by walking around it and looking at it, or following it to its end. You jump in and let it flow past. You feel the force of it hit you as things float by.

In other words, the Stream replaces topology with serialization. Rather than imagine a timeless world of connection and multiple paths, the Stream presents us with a single, time ordered path with our experience (and only our experience) at the center.

To me, the TikTok FYP is the internet as a visual Stream, just as Wikipedia might be our most-used textual Garden. TikTok puts everything on one timeline, and takes away your ability to order your visual experience beyond the indirect levers of likes, comments and saves. And so when I “strike gold” on TikTok, it’s because I’ve been knee-deep in that Stream, panning and panning for gold, to eventually find something that I think it’s cool or funny enough to send to my friends.

Quick interlude: I think it’s important to note that the Stream has become the default form in which content is presented: our Twitter timelines, Instagram feeds, email inboxes, etc etc etc, are presented this way. A lot of us younger internet users never knew a time before this, never knew what it was like to wander the internet, instead of scroll through it. If you’re interested in the Garden alternative, try this, or this.

Social uses for social media

One really interesting implication from my honors thesis research (that didn’t really make it into the final product other than at the end) was a discovery that interviewees used TikTok either for social uses or isolated uses. Those using it for social uses tended to share many videos with their friends either through in-app DMs or via sending links to the videos on other messaging platforms. Those who did this most often were those who made sure to send videos to friends or open their DMs to respond to all the TikToks their friends had sent. They enjoyed a lively social network, sustained by the connective act of sending a video to someone they thought would appreciate it.

Others tended to describe their TikTok use as more isolated. One person said that his usage was “an experience that is between (him) and TikTok”. Another interviewee mentioned that he would primarily consume content on TikTok by himself, while eating or in the bathroom and so on. This description of isolated use often correlated with feeling like they were “losing time” on the platform, or like TikTok/ByteDance was manipulating them or brainwashing them to spend more time on the app.

This division of social versus isolated uses of TikTok thus seems to map onto being optimistic or pessimistic about one’s ability to preserve agency on the platform against the algorithm. I couldn’t look into it further within the parameters of my study, but my hypothesis for now would be that when the algorithm and the platform are mainly serving a function of linking one to friends and family, they seem less important and powerful in the face of the maintenance of important social relationships.

Keeping that in mind, I think it’s healthy that whenever I “strike gold” on TikTok, my first response is to share it with as many friends as I can who might find it interesting. I want to keep using TikTok to the extent that the TikToks I come across can continue to be tokens of affection I use to energize my social relationships. Without maintaining that motivation, I think that TikTok would just become an unrewarding timesink.

Personalization is labor

Another theme I want to highlight here is labor. I’m using the metaphor of panning for gold deliberately, to bring to mind that entering the Stream involves work.

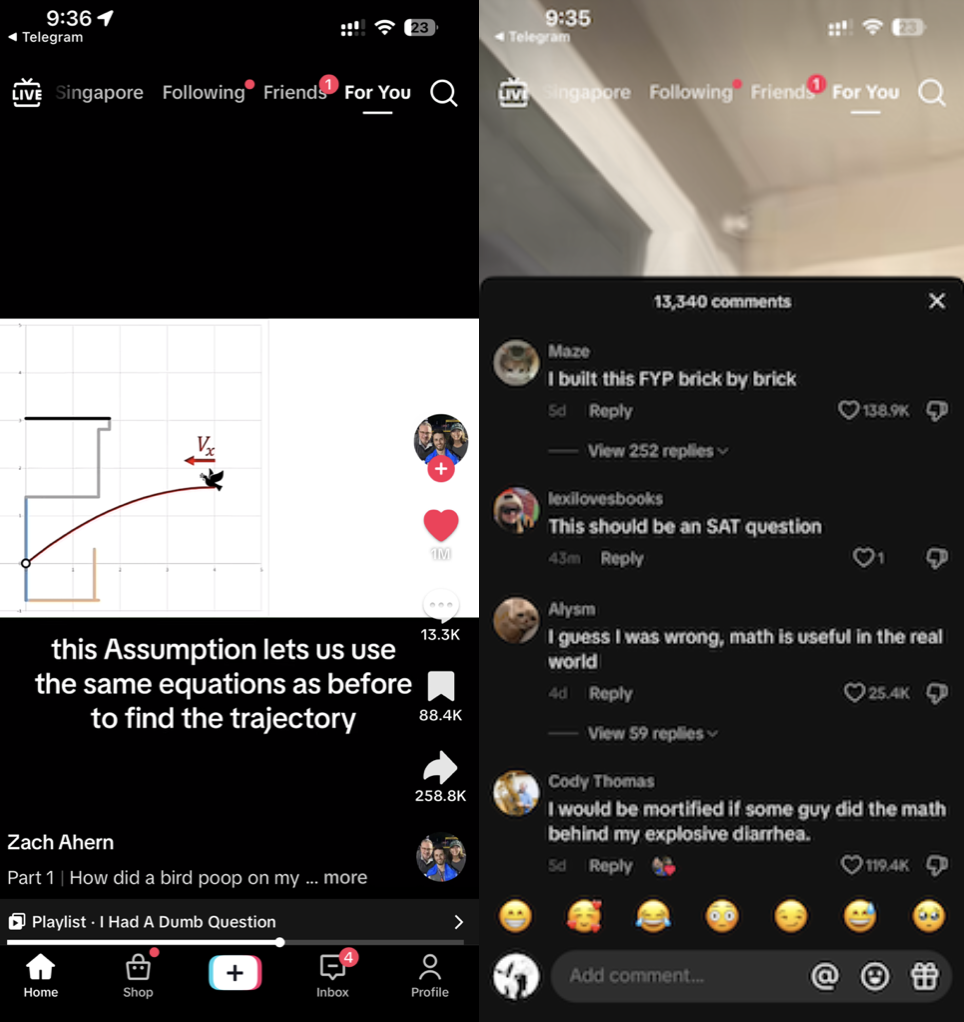

You can see that colloquially as well: Here’s another gem I sent to everyone I know, where some guy finds bird poop on his balcony window, and decides to calculate where the bird would have to be to make that poop stick. Again, just watch it, if only for the academic facts on penguin poop velocity: https://www.tiktok.com/@zachahern1/video/7377964014246186283?_r=1&_t=8nBLeWwd4XH

The top comment is “I built this FYP brick by brick”. There’s labor involved here, and also a sense of self-deprecation and self-congratulations. People attribute the recommendations they get from the TikTok algorithm to themselves, their habits, preferences, and interactions with the app. And all that is put under the characterization of labor.

Being a user means doing work

This was a theme that kept popping up when I did the interviews for my thesis. I found that no matter what users thought of the algorithm, users always frame their own active role in shaping their experience on the app. Even the users who most see the algorithm as a tech product, do not see it as a product that comes finished right out of the box: they emphasize that it is a tool they must actively learn to wield, and on top of that they must maintain it to continue getting a satisfying experience.

For the users who focused on the algorithm not as an apolitical tool but as a vehicle for ByteDance’s profit-driven motives, they took on the burden of peering past the individual videos being recommended, to try to understand how exactly they are being manipulated in the company’s interests. The user is always putting in work and effort to better discern the inner workings of the algorithm and how that might affect their experience. That might manifest in feeding the algorithm more information by engaging, limiting engagement to stave off its profit-driven motives, or simply evaluating content that they would find beneficial or detrimental based on their self-image.

I ended off my thesis paper with a call for more research into comparing and contrasting “the algorithmic imaginaries of users who use social media more for socials, or more for media.” Looking back, I regret drawing that hard line between the social and the media in ‘social media’. Any of my Media Studies friends could tell you that media is always social, even when the social relationship involves just you interacting with yourself and your selfhood. From a 2022 study by Cornell researchers Aparajita Bhandari and Sara Bimo, by virtue of TikTok’s deep personalization to each individual user, the algorithm repeatedly confronts users with various aspects of their own personas — users’ sense of humor, interests, physical appearance, geographical origins, etc. — via curating content.

While I think there is something introspective to seeing the algorithm as a mirror for the self, I think it’s far healthier to treat the Stream as a connective force with others, rather than an expansive projection of my ego. So I’m ending off with a bid for connection too: Watch this TikTok, I swear it’s funny.

Cross-posted on Substack here