In April this year, I went on a trip to Yosemite Valley with a couple college friends. While hiking to Columbia Rock, we caught up to these two women hiking the same way up, blaring club music from a phone tucked into one of their pockets. I remember feeling jarred, and then annoyed. Spring in Yosemite is supposed to look green, sunny and lush — and it’s also supposed to sound that way, all chirping birdsong and the roaring rush of waterfalls. We ended up speeding up to lose the two women and their technobeats.

We later met the exact opposite of those two women: a man going the other way down the trail, Sony wireless noise-cancelling headphones wrapped securely around his ears. I remember my friends and I judging him so hard as he went by: who comes to hike in Yosemite Valley only to put on noise-cancelling headphones? And they were the viral noise-cancelling ones too, so he was definitely hearing either just his music or nothing at all. No birdsong, no waterfalls. I wonder how his experience differed from those virtual hike simulations loaded up on the treadmills at the gym.

Seeing is believing, right? But I wonder if seeing is all there is to objective experience. To me, those hikers were destroying their experience of Yosemite Valley, either by bringing in music that drowned the natural sounds of the trail, or by blocking those sounds out entirely. I would extend this to a certain prioritization of the visual, or maybe a better way of putting it would be a deprioritization of the non-visual senses like hearing, touch and smell.

In the context of natural history, Foucault called this the “nomination of the visible”. To perceive the truth and articulate it was based on observation, narrowed down to sight (The Order of Things, p. 144):

Hearsay is excluded, that goes without saying; but so are taste and smell, because their lack of certainty and their variability render impossible any analysis into distinct elements that could be universally acceptable. The sense of touch is very narrowly limited to the designation of a few fairly evident distinctions (such as that between smooth and rough); which leaves sight with an almost exclusive privilege, being the sense by which we perceive extent and establish proof, and, in consequence, the means to an analysis partes extra partes acceptable to everyone…

What he’s basically saying is: From mid-17th century Europe, there was a “division of the sensible”. The world had to be ordered, classified, taxonomized, and that had to be done objectively. Sight came to be understood as the most objective way of doing this, with other senses considered too imprecise or subjective. An easy way of getting this might be noticing how we might say “taste is subjective”, referring to both taste as physical sense, and taste as aesthetic or preference. In contrast, we have a heavy emphasis on an “eyewitness account”, on the assumption that what someone sees is likely an accurate reflection of reality.

And yeah, anyone could tell you that sight isn’t the only sense that determines experience. But I never really felt that so viscerally before, till we went for a Sunset Walk tour with the Yosemite Conservancy. At the very beginning of the walk, the guide urged us, “While we walk through the valley, ask yourself: what is this national park doing for you? What did you get? Why did you come?”

As we walked towards Cook’s Meadow in the golden hour of the valley, he named every tree and plant we passed, with both the scientific English name, but also the name that the indigenous Ahwaneechee tribe used. The tour was incredibly visceral, rooted solidly in the physical experience of touching, smelling or hearing things. When we passed a white pine tree, he broke off a couple needles and made us smell them. It was a sharp citrus bite, and we said it smelled like lemons — I remember the guide’s excitement when he said that that was Vitamin C, and that the indigenous tribe living in the area would boil the needles into tea to treat arriving miners/forty-niners that had signs of scurvy. He explicitly helped us link the physical smell of white pine to the local, generational knowledge that indigenous peoples had — lived experience that doesn’t fit within the paradigm of Western medicine but is validated by it anyway.

The tour was incredible, I can’t emphasize it enough. He told us about everything from black oak to Steller’s jay, from the geological formation of the valley to the history of Chinese railroad workers laboring to create paths for tourism into the park.

At the end, the guide made a joke that’s stuck with me for a while. It was just an off-handed comment: “You can’t feel this with an Apple Vision Pro, right?”

And yeah, he’s right. That’s my reason for visiting Yosemite, and my reason for being incredulous at the two women blasting music or the guy with his noise-cancelling headphones. I drove those 3.5 hours from Berkeley to be sensorily engaged. I think that understanding comes from embodiment, from feeling an experience in more ways than just sight. There’s just something so different about learning this way: we were given a crushed up piece of California bay laurel and told to smell it. I nearly choked on the heavy spiciness that hit the back of my throat. But when the guide told us that the indigenous peoples would use this plant to line their acorn stores to keep insects away — like, yeah, of course! That’s what I’d use this for too, after touching it and smelling it. It was a fundamentally different kind of understanding from simply seeing it in a documentary, even if I watched it through the Apple Vision Pro.

Why this emphasis on the visual though? Or, in Foucault’s terminology, why was the visible nominated, and not the heard or the touched? I think that the answer to these questions has something to do with the development of audio-visual/perceptual technologies through history, and how they have intertwined with biological sight, to create this illusion that seeing reveals reality.

Since the advent of print, pictures and illustrations were considered effective tools for communicating across time and long distances. From scholar Benjamin Schmidt’s work on Dutch exotic geography, for Europeans at the turn of the 18th century, “seeing was inherent to the discovery of the early modern world, and knowing the world … came via processes of observation.” (p. 84) And this observation was commodified by Dutch geographers and illustrators, who built a lucrative industry off of selling spectacular (often fictionalized) engravings and prints of China, India, North America, the Middle East, and so on. For the European consumers of these travel books, it didn’t really matter if the pictures they bought were truly accurate to reality — what mattered was an aesthetic of accuracy, a sensing that this was an eyewitness account of fabulous places overseas. What mattered was a sense that faraway places were suddenly within sight, because that meant they were within reach.

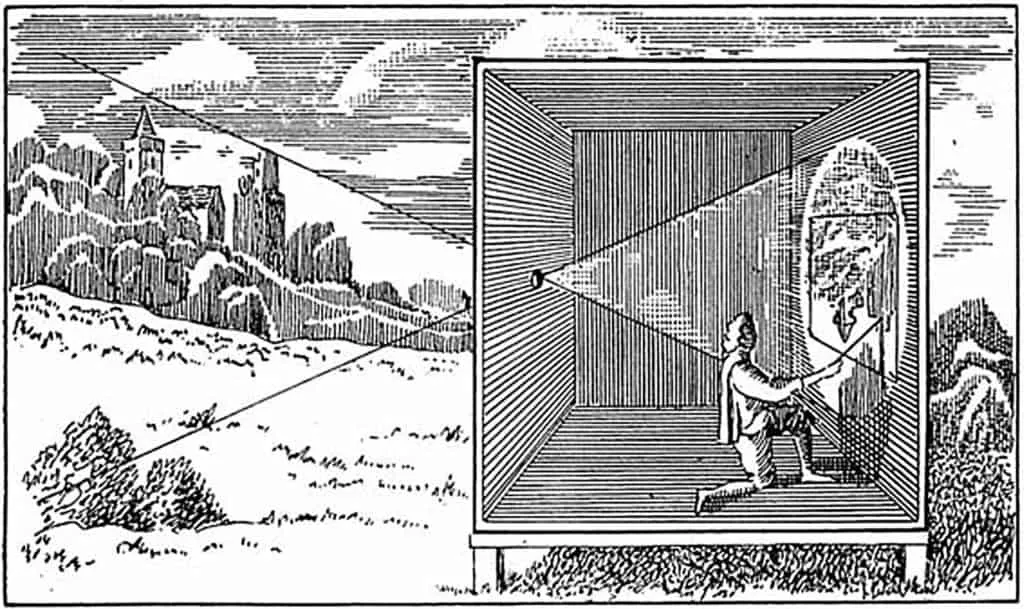

Post-print visual culture was one that elevated sight to the point of isolating it, particularly with perceptual technologies that continually maintained that division between sight and the other senses. We see that isolation in the camera obscura, or a pinhole camera.

From NYU professor Nicholas Mirzoeff, the camera obscura is associated with a fixed, monadic point of view. The individual observer is in an isolated dark room, detached from the world, perceiving the outside only through the rays of reality that come through the pinhole. This technology promises a perfect visual reflection of the world outside — objectivity! — only through withdrawal and purification from the world itself, and all other information you might gain from your other senses.

However, that promise relies on the assumption that the human eye can be trusted, and that what I see with my eyes is what you see with your eyes as well. From art critic and scholar Jonathan Crary, that started to crack under further research by scientists and physiologists like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. One of their most important areas of research was called binocular disparity — the realization that each eye sees a slightly different image at a slightly different angle. It might sound really ‘duh’ to us now, this idea that we have two eyeballs but one field of vision, but this discovery made seeing and perceiving, once thought of as objective and fixed, instead shockingly personal and subjective. The general public experienced this via stereographs, popular predecessors to photographs, which displayed two images of the same subject, captured from slightly different angles, through two lenses, one for each eye. Seeing through the binocular lenses, the observer would see instead the illusion of a whole image, that was startlingly real. This technology relied on the mind’s ability to reconcile binocular disparity and reconsolidate reality out of two different images.

Vision was detached from a stable external referent, because there’s two images merged into the illusion of one, in a process that our brain apparently does automatically/unconsciously. On top of that, vision was detached from a stable fixed perspective — we have 2 eyeballs! — and if there is no one angle we’re looking out from, then it became doubtful that we could ever ensure that what one sees is truly a collective reality.

This uprooting of vision from the fixed external referent and fixed perspective of the camera obscura generated a lot of unease. That unease was seemingly resolved by the invention of the photographic camera, when technology eventualy outpaces human vision.

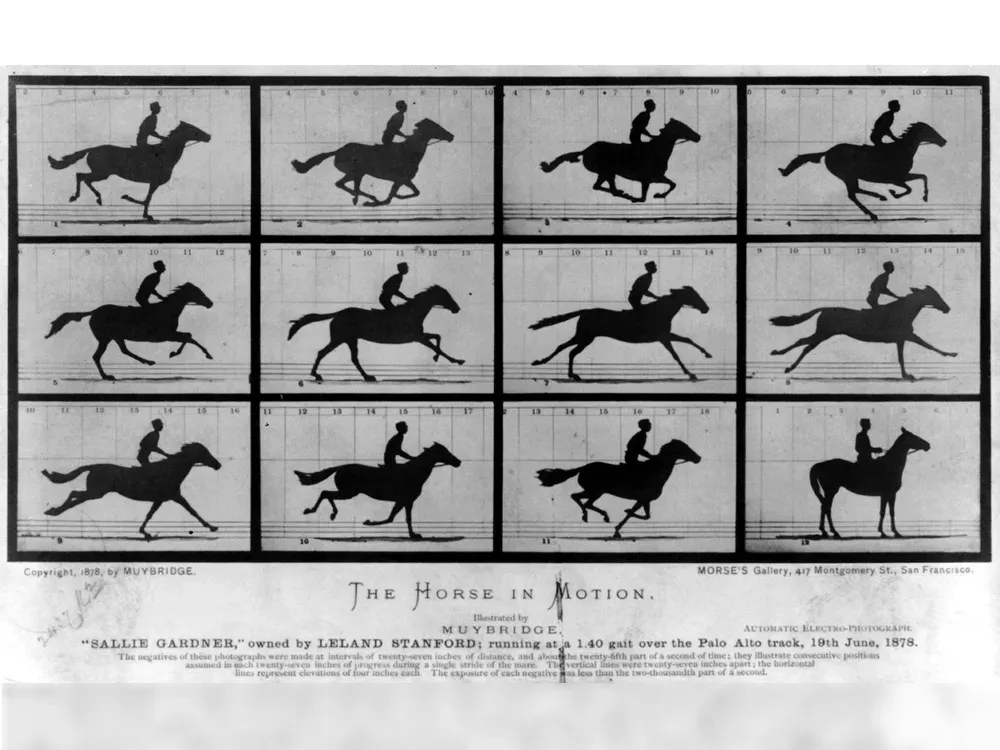

From Rebecca Solnit’s River of Shadows, Eadweard Muybridge develops a way to take successive photographs of a horse in motion at fractions of a second, isolating frames of movement far faster than the human eye could perceive. This comes on the heels of scientific research quantifying the various mechanisms of the biological eye — its reaction speed, time till fatigue, etc. Muybridge’s chronophotography presents a mechanistic solution to all the physical limitations of the eye that these studies had found, through a disassembly and reassembly of time that relied on tricking the eye to see movement at 1/10 of a second. This perceptual technology seemed to present the truth of the world — reduced to perceptual units that the eye could not capture, and pushed the concession of objectivity to the machine.

This is seen in the crisis of representation that followed the release of The Horse in Motion: Artists were flummoxed by the truth of the full range of motion of a horse’s gallop, one that included a still frame of its legs curled up off the ground like an ugly dead spider, but not the commonly represented pose of a horse with front and hind legs stretched out. The artist Meissonier even repainted one of his most famous paintings depicting a galloping horse in accordance with Muybridge’s photos, but wryly had to acknowledge that the very mission of painting had changed — it could no longer see itself as aligned with science in pursuit of objective truth, for science had outpaced it in freezing time. The photographic camera thus develops the shift to physiological vision in the stereograph, by exploiting it. Not only that, but it mystifies the involvement of the body that had made observers so uncomfortable with the stereograph, and presented instead a mode of perception that articulated the seeming wholeness of the world, despite that wholeness being reconstructed by a machine, after a mechanistic disassembly out of the bounds of human perception. The photographic machine, therefore, becomes the site of objectivity, through which objective perception is attained.

TLDR; the shift from camera obscura to stereograph problematized perspectival vision attained through disembodied detachment, and prompted the shift to physiological vision — a new, mobile, embodied and binocular way of seeing and seeing perception. In this, objectivity seemed uneasily out of reach for humans each perceiving their own subjective versions of reality. This was seemingly resolved by outsourcing objectivity to the photographic camera, which seems to portray a whole truth, mechanistically reconsolidated for the human observer — a new way of seeing that the machine must mediate.

I went for a free guided tour at an Apple store this May, and saw that same mechanistic reconstruction of reality. Sitting at a white counter with a store employee (really so Apple, the sleek design coupled with a guy in a casual t-shirt), I clamped the giant contraption around my head and looked out at the world. The employee went to great pains to describe how users were meant to be able to look ‘through’ the device while also looking at the digital interface within it. All the content in the app thus seemed like an overlay on the actual physical environment around me — I spent a funny moment layering different app windows on top of my partner’s face in real life.

But it was really obvious that what I was seeing of my surroundings behind the apps was grainy, almost pixellated. When the employee said we could ‘look through’ the device, I assumed that he meant that I was literally seeing through the glass, like spectacle lenses. After clarifying with him, though, that wasn’t the case. What I saw of my physical surroundings when wearing the Vision Pro was actually digitally recreated by its cameras.

In other words, it was a breaking-up of reality into different points of view from cameras, and then a reconsolidation for the user, by the machine. It was performing the exact thing that a stereograph did, except with the involvement of the human body instead outsourced to machine learning: instead of bin-ocular vision, it was a machinic multi-ocular vision.

Other than the stereograph, I also see echoes of the camera obscura in this new technology. The way the device blocks out your vision entirely and relocates you to a disembodied realm of windows and apps really does feel like the sensorial detachment of the camera obscura dark room. To be in touch with this digital reality, one must withdraw from the physical world first.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that I see the Apple Vision Pro as another in a long line of perceptual technologies, that have developed alongside us over time, but never really let go of this obsession with sight and vision. I know that the major difference between this new technology and the older perceptual technologies mentioned above, is that objectivity is no longer the goal. In that moment in the Vision Pro guided tour where a bird seems to land on your finger, you could think that you can interact with it, but you’re not under the illusion that this is truly reality. And Apple doesn’t want you to be. Objectivity is no longer the goal because that isn’t Apple’s business — the personalized subjectivity that so destabilized people during the time of the stereograph is now desirable, fantastical, and profitable.

I want to return to Yosemite Valley. There was a moment towards the end of our sunset tour that the guide told us to look at Yosemite Falls and asked how it made us feel. The word ‘awe’ kept coming up in the responses, as we stared up at the point where the upper falls plunged off that steep drop, roaring over a plateau and then disappearing into the tops of the trees lining Cook’s Meadow. I remember that, but I also remember the power of the waterfall in the sound of it, but also the serenity of the meadow and its birds and solid planks of wood beneath my feet.

Awe, according to a class I took with renowned professor Dacher Keltner, is a mix of reverence, fear, and submission. He would use the phrase ‘feeling small’ to describe it, noting that the word ‘awe’ has its roots in the early Middle English ‘age’, meaning dread. Awe wouldn’t be awe without a touch of terror.

I don’t think technologies like the Apple Vision Pro could make us feel small. I think that when vision is isolated like that, it detaches us from the realities of what we’re seeing while giving us the illusion of power and control over what is seen. It’s a feeling like I could see, change, consume the world just by tapping my thumb and index fingers together. That’s probably what the 18th century European elite felt when they bought Dutch exotic geography. Exotic peoples and things were laid out like a catalogue, like consumable things. And they became consumable things because of both their representation by Dutch illustrators, and the perceptions of the buyers of these illustrations, for whom it was fashionable to collect representations in place of collecting the peoples and things themselves.

What I want are experiences that I don’t have so much power and control over that they become acts of consumption. I want experiences that are awe-inspiring, and I recognize that getting there requires being entirely embodied, being entirely sensorily engaged. To get to that feeling of fear-reverence involves giving up any claims to stable external referents or fixed perspectives or the digital mimicking the physical, and settling into the fear of our own embodied subjectivity, without giving in to the temptation of outsourcing mediation to a machine. It involves trusting the body, not just the eyes.

If you got all the way here, go touch some grass!

This article draws heavily on content taught in Media Studies 111C: Audio-Visual Media History, taught by Professor Matthew Berry at Cal, and Psychology C162: Human Happiness, taught by Professor Dacher Keltner.

Cross-posted on Substack here